Fife Pictorial & Historical: Vol. II, A H Millar, 1895

pages 287 - 295

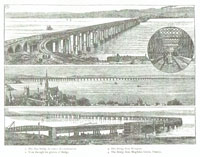

[The Tay Bridges]

The following account is based upon the articles which appeared in the Dundee Year Book for 1887, and on a paper read at the Institute of Civil Engineers by Mr F. Kelsey, one of the superintendents at the construction of the second Tay Bridge.

With Mr (afterwards Sir Thomas) Bouch originated the idea of bridging the Tay at Dundee. As engineer to the Edinburgh, Perth, and Dundee Railway Company, Mr Bouch, from his experience, witnessed the inconvenience and danger attendant on the working of the Tayport and Burntisland ferries. The system was costly and clumsy, and to obviate these two drawbacks to the successful working of his directors' railway he was led to seek for a remedy. In 1854 Mr Bouch propounded his scheme of bridging the Forth and Tay. The directors were amazed at the boldness of the conception, and when the idea became public property its originator was looked upon as a dreamer. Scottish caution was scared for a time. Seeing what engineers had accomplished in the past, not only in subduing the forces of nature but also in utilizing them in the furtherance of great undertakings, it was very disheartening to Mr Bouch that his pet scheme was so coldly received. He did not despair, however, of ultimate success, so far at least as the Tay Bridge was concerned. He waited with patience, and by and by the 'wild dream' of 1854 began to appear in the eyes of professional men, as well as to the directors and others interested in the scheme, in a less fantastic light. Year after year passed, however, and Mr Bouch had to struggle on, striving to convince pessimists of the feasibility of his plans.

Mr Bouch was fortunate in having the thorough sympathy and active support of Mr (now Sir Thomas) Thornton, solicitor, Dundee, and both gentlemen worked hard in bringing the Tay Bridge scheme before the public. In October 1863, the first step was taken in connection with the project, when a meeting was held in Mr Thornton's office, at which Provost Parker and a few of the leading citizens were present. A year elapsed, and the Dundee Advertiser announced on the 18th October 1864, that the promoters intended to apply for a Bill to sanction the erection of a bridge across the Tay between Newport and the Craig Pier. At this point the Tay was to be crossed in 63 spans. At the fairway the height was to be 100 feet above the level of high water, and before the Dundee side was reached this height was reduced to between 25 and 30 feet. Instead of curving to the east the direction was to the west, and the junction with the Perth line was to take place at the east end of Magdalen Green. This announcement caused what might be called a sensation. The Town Council and Harbour Trustees of Dundee took up an uncompromising attitude against the scheme; the Scottish Central and Scottish North-Eastern Directors were anxious to prevent a rival from becoming stronger than themselves; and the Perth Town Council saw in the proposal the utter annihilation of their harbour. The Bill, however, served the purpose of forcing both friends and foes to declare themselves, and it was only withdrawn after the North British Company had openly espoused the project, with a view to a practical development of the system both on the north and south of the Tay. Accordingly in the next session of Parliament (1865-66) a second Bill was brought forward by Mr Bouch and Mr Thornton, under the auspices of the North British Railway Company. This time the bridge was to be connected, not with Tayport only, but also with Leuchars, and it was to cross the Tay from Wormit Bay on the south to a point considerably west of the Binns of Blackness on the north. From that point the line was to be carried to the high ground over the Dundee and Perth Railway, and running eastward it recrossed that line, outside of which it ran until Buckingham Point was reached. Here it again crossed, and ran to the centre of the town through the gardens attached to the residences on the south of the Magdalen Yard Road, the Perth Road, and Nethergate, then crossing Sea Wynd, passed through the ground behind St Paul's Free Church, and crossed Union Street to the south of the Thistle Hall. From there it proceeded through the then old buildings between Nethergate and Fish Street, crossed Crichton Street to the south of Mather's Hotel, and ran into a magnificent central station, within the area of which the Town House was included. From this central station the route eastward was by Dock Street. It was intended to divert this street to the south by the railway, which, running eastward, was to join the Arbroath line to the north of Camperdown Dock.

The Esplanade scheme was associated with the Tay Bridge because station accommodation could not be got unless the solum south of the Caledonian Railway was made up. In this new Bill of 1866 the North British conceded the right of the town to the solum of the river, and thereby did away with opposition on the part of the Town Council. It was agreed that the Council should become the absolute owners of the Esplanade. The town itself, after agreements with both Railway Companies and the Harbour Trustees, ultimately got a Bill passed for the construction of the Esplanade. Under this Bill the inhabitants of Dundee resumed possession of the foreshore, extending to nearly a mile in length, and secured a spacious street of 100 feet in breadth, the one half of which next the river would be set apart as a public promenade. All the ground made up north of the promenade was to be used for railway purposes only, the Caledonian Railway Company paying £13,000 and the North British Company £13,000 for the space occupied by them. The Harbour Trustees also contributed £13,000 towards the Esplanade expenses.

This new Bill of the North British Railway Company, however, was destined not to pass. Opposition appeared on almost every hand. It was allayed by the promoters of the Bill, who offered some tempting quid pro quo to their opponents, which was generally accepted. But the scheme was too magnificent, and the shareholders of the Company began to have doubts of the practicability of carrying out the proposals in their entirety. The central station part of the scheme was ultimately dropped, much to the chagrin of owners of property on the proposed route; but this concession on the part of the directors did not remove the doubts of the shareholders. The chief causes which led to the ultimate withdrawal of the Bill, however, were (1) the amalgamation of the Caledonian and Scottish North-Eastern Railways, and (2) the want of funds in the treasury of the North British Railway Company.

But the promoters were not disheartened. The public opinion of Dundee had grown, and that which had at the outset been derided as a vision was now regarded by the bulk of the community as both practicable and beneficial. Accordingly in 1869-70 another scheme was submitted to Parliament. The bridge was to be thrown across the river from Wormit to Buckingham Point, the Fife connection being made by a new line from Leuchars. The station was to be erected on the solum acquired by the Town Council under the Esplanade Act and relative agreements, and upon such a level as would connect it with the bridge by a gradient of 1 in 60. With the Arbroath section of the Caledonian system the station would be connected by a tunnel crossing under South Union Street and adjoining properties, curving round the north-west corner of Earl Grey Dock, and thence passing under Dock Street, to emerge upon the Arbroath line about the east end of Victoria Dock. The Bill came before a Select Committee of the House of Commons on the 17th of March, and from the unanimous support which the scheme received from all the witnesses the preamble of the Bill was proved, and on the 15th of July following the royal assent was given to the measure.

Although the public bodies in Dundee and elsewhere, as well as the community at large, were by this time thoroughly convinced of the practicability of bridging the Tay, there still remained a number of isolated pessimists, who were continually uttering predictions of disaster and ruin to the bridge, and, indeed, some went so far as to assure the world that it could never be erected. A look at the plans did not comfort these individuals. The extraordinary length of the bridge - its great attenuation - made it look more slender than it really was.

A very short description of the first Tay Bridge is required. Its length was 3450 yards, and it consisted of 85 spans of the following dimensions: 11 spans, each 245 feet; 2 spans, each 227 feet; 1 span, 166 feet; 1 span, 162 feet 10 inches; 13 spans, each 145 feet; 10 spans, each 129 feet 3 inches; 11 spans, each 129 feet; 2 spans, each 87 feet; 24 spans, each 67 feet 6 inches; 3 spans, each 67 feet; 1 span, 66 feet 8 inches; 6 spans, each 28 feet 11 inches. The piers were 85 in number, of which the first fourteen were of brick, the remainder being formed above high-water level with tiers of cast iron columns, bolted together vertically by bolts and nuts, and connected laterally by means of cross-bracing and struts of wrought iron. The number of columns in the group on each pier varied from three to six. Those under the largest spans were formed of six columns, bolted to base pieces, which were bedded in stone. The lower portion of these piers consisted of concrete, brickwork, and masonry. At piers 28 to 41 the girders were raised so that the lower booms were on a level with the upper booms of the girders on the north and south. This gave additional headway for vessels passing below the bridge. The headway was 88 feet from high-water mark. The upper structure was of wrought iron lattice girders, except one span on the northern portion, which was crossed by bowstring girders. Messrs Charles de Bergue & Co., of London, were accepted as the contractors by the North British Railway Company, the price to be paid that firm being £217,000, and the time specified for the completion of the bridge being three years. Owing to the illness and subsequent death of Mr Charles de Bergue, the contract was transferred to Messrs Hopkins, Gilkes, & Co., of Middlesborough. In consequence of having to transfer the contract from one firm to another great delay was experienced, and when the bridge was finished it was found that, instead of three years, the bridging of the Tay had occupied six years; and that the cost of the bridge had been £350,000 instead of the contract price.

On the 22nd of July 1871, the first stone of the bridge was laid on the Fifeshire side, and on Tuesday 25th September 1877, six years and thirty-three days afterwards, the works had so far advanced that the directors, engineers, and contractors were able to cross the structure in a train. This was the first train which ever crossed the Tay Viaduct. Though the works were sufficiently forward to allow of the train being run across, much required to be done to the structure before it was ready for general traffic, and it was not till the 31st of May in the following year that the formal opening took place.

The Tay Bridge was the engineering wonder of the day. The people of Dundee were proud of the bridge. For the first time in their history they felt that they were no longer on a railway siding, but were in direct communication with the principal towns of the kingdom. To the travelling public, too, the opening of the bridge was a great boon. The new route took an hour off the tedious journey between Dundee and Edinburgh, and the run into Fife was accomplished in half the time formerly occupied. The excellent train service which the North British Railway Company inaugurated had the effect of spurring on the Caledonian Railway Company in the direction of accelerating their trains to the south and west, and compelled them to provide improved railway carriages. The goods traffic of the North British increased beyond the expectations of everyone, and the dispatch which traders experienced in the delivery of goods made them feel that the hopes held out by the promoters of the bridge had been understated. The bridge thus formed a most important link in the East Coast route, and its success proved beyond doubt that when a similar connection was made between the shores of Fife and Linlithgow immense advantage would accrue not only to Dundee, but to the whole of the towns on the north-east coast. But disappointment was in store for those who had formed so sanguine hopes of the utility of the bridge. Little more than eighteen months had passed away when there occurred a terrible calamity, the news of which was received with horror and dismay all over the kingdom. On the memorable night of Sunday, the 28th December 1879, in the midst of a fearful hurricane from the south-west, the large girders fell, carrying with them to the foaming waters beneath a train and about ninety human beings, not one of whom survived to tell the tale. Happening as it did when darkness had set in, the extent of the calamity was not definitely known till late next morning; but when daylight came thousands of eyes were directed towards the centre of the bridge. The sight which met the eye was depressing in the extreme. The whole of the thirteen large spans had disappeared, and the broken stumps of the columns which had supported them, but which had proved insufficient when the crucial moment arrived, stood up in all their desolate loneliness. The storm which had raged with so much fury on the previous night had entirely abated, and the river was so calm and unruffled that one could hardly believe that an accident of so mournful a nature had taken place only a few hours before, and that nearly a hundred human beings had been swept into eternity without the least warning.

The appalling accident was looked upon as a national calamity. The utmost sympathy with the sufferers was expressed by the people in all parts of the country, and the Queen telegraphed to Provost Brownlee that she was inexpressibly shocked, and felt most deeply for those who had lost friends and relatives in the terrible accident. An official inquiry into the circumstances attending the fall of the bridge was ordered by the Board of Trade. The commissioners appointed were Mr Henry C. Rothery, wreck commissioner; Colonel W. Yolland, chief inspector of railways; and Mr William H. Barlow, president of the Institute of Civil Engineers. The commissioners at once proceeded to Dundee, and personally inspected the ruined structure. Evidence was afterwards heard by the commissioners in the Dundee Sheriff Court. Many witnesses were examined, chiefly as to the facts and circumstances attending the fall of the bridge, and the inquiry was adjourned from 6th January to 26th February. When it was resumed, evidence was led as to alleged undue speed of trains upon the bridge, and to facts in connection with the erection of the structure. The commissioners sat nine days altogether in Dundee, and adjourned to meet at Westminster on the 19th April, to hear the scientific evidence, and to ascertain from experts the effects of wind pressure, etc. The inquiry, including the sederunts in Dundee, lasted twenty-five days, and was considered one of the most searching and exhaustive investigations ever conducted in this country.

Six weeks after the close of the inquiry the commissioners submitted their report to the Board of Trade. They reported that no evidence had been given to show that there had been any movement or settlement in the foundations of the piers. The wrought iron had been proved to be of fair quality, while the cast-iron had also been fairly good, though sluggish in melting. For the work they had to do, the girders, in the commissioners' opinion, were fairly proportioned. But the iron columns, though sufficient to support the vertical weight of the girders and train, had been, owing to the weakness of the cross bracing and its fastenings, unfit to resist the lateral pressure of the wind. There had been imperfections in the work turned out at the Wormit foundry, and these were due in great part to want of proper oversight. The commissioners were not satisfied with the supervision of the bridge after its completion, and they were of opinion that if by the loosening of the tie-bars the columns got out of shape, the mere introduction of packing pieces between the jibs and cotters, which had been spoken to by witnesses, would not bring the columns back to their positions. It had been proved that trains were frequently run through the high girders at a much higher rate than that sanctioned by the Board of Trade - viz., 25 miles an hour. After careful consideration, they came to the conclusion that the fall of the bridge had been probably due to the giving way of the cross bracing and its fastenings, and that the imperfections in the columns might also have contributed to the same result

After the fall of the bridge very little time was lost by the directors of the North British Railway Company in preparing plans for its reconstruction. Scarcely six months elapsed from the time of the calamity before the North British Railway (Tay Bridge) Bill was brought before Parliament. On the 8th July 1880, it was ordered to be read a second time, and committed to a special committee of seven members. On Tuesday 20th July, the committee sat for the first time to take evidence. The chairman, Sir Massey Lopes, in opening the inquiry, said the committee felt that the question was one of more than usual responsibility, and therefore he thought it very desirable that they should direct the special attention of counsel to the order of reference, and to request them to satisfy the committee on the following points: - (1) The expediency of rebuilding the bridge in its present position; (2) whether there was any more suitable site; (3) the interest of the navigation; and (4) the security for the permanent safety of any bridge if authorised. In asking the committee to pass the Bill the promoters would have to satisfy members on these four points.

Mr Walker, general manager of the North British Railway Company, gave it as his opinion that no more suitable site could be had than the one on which the old bridge stood. It put important towns such as Cupar and St Andrews in direct communication with Dundee, while Newport and Tayport, where many of the Dundee business men resided, would be placed within easy distance of that town. Between the towns and suburbs mentioned there was very large interchange of traffic, and it was of importance that the railway communication should be as direct as possible. The bridge, Mr Walker stated, could not be placed further down the river. The local witnesses examined, including many leading Dundee merchants, were all of opinion that the bridge should be constructed on the old site. It was shown that the small number of vessels that went up the river to Perth would not be incommoded by the erection of a bridge at a safer altitude than the previous structure, and the advantages to be obtained overbalanced any objections that were offered.

Mr James Brunlees, CE, submitted plans for the reconstruction of the bridge. His proposals may be briefly summed up as follows: - He was to double the piers of the bridge by sinking a cylinder on the east side of each of the old piers; to carry up the new cylinder above high-water mark, and there to connect the old and the new with arched brickwork. On this saddle he proposed to build a brick column sufficiently wide to carry two sets of girders and a double line of rails. A wider basis than in the case of the old bridge would by this method be obtained, and the strength of the structure to resist lateral pressure would be materially increased. A height of 77 feet instead of 88 feet from high-water mark to the lower boom of the girders was to be provided in the case of four of the spans over the fairway. On the other portions of the bridge Mr Brunlees proposed that the permanent way should be laid on the upper booms of the girders. The width of the spans at the fairway was to be 245 feet. The new caissons were to be of the same size as those of the old bridge, and there were to be to feet between the two. Mr Brunlees proposed to erect bowstring girders 20 feet high over the fairway. By adopting this pattern of girder he considered he would get much less exposure to the wind and more lateral stiffness than in the girders which had fallen from the first bridge. The girders were to be doubled, and were to be capable of resisting 200 lbs. to the square foot of wind pressure, while the piers as designed were to be capable of resisting a pressure of 900 lbs. per square foot. The work of reconstruction he proposed to carry out at a total cost of £356,323. This plan was carefully considered in committee, but, as the Board of Trade regarded it as a dangerous method to join the old work to the new, it was ultimately rejected, and the committee reported unfavourably regarding the Bill.

The rejection of the Bill of 1880 was very discouraging, but the North British Railway Company, knowing the importance of restoring the connection between Fife and Forfarshire, which had been so suddenly interrupted, determined to devise another plan. Accordingly, in August 1880, Mr W. H. Barlow, CE, of the firm of Barlow & Sons, London, was asked to report upon the best method of reconstruction which would secure the actual and permanent safety of the structure. After a series of elaborate experiments upon the existing remains of the bridge, Mr Barlow advised that the portions which were still intact should be entirely abandoned, and that a new bridge should be built from shore to shore. A new Bill was prepared embodying his plans, and was brought before a select committee of the House of Commons on 10th May, 1881. With a few alterations and additions suggested in committee the Bill was ultimately passed. In November 1881, the contract for the building of the new bridge was entrusted to Messrs William Arrol & Co., Glasgow, and the work was carried out by that firm to the satisfaction of all concerned.

In their design for the new bridge Messrs Barlow adopted no untried principles of engineering, but adhered throughout to well-known and established methods. The Tay Viaduct is simply a pier and lattice girder bridge, and but for its extraordinary length and unique situation, has no distinguishing characteristic. What the engineers aimed at was to obtain stability, combined, as far as possible, with graceful outlines, and to reduce to the smallest degree the weight on the basal area of the foundation. The brick and concrete cylinder of each pier is encased in a strong wrought iron caisson up to about low-water mark. It is then continued upwards, the shaft being faced with Staffordshire brick, impervious to water. Above high-water mark the two cylinders are tied together by means of a strong connecting piece, which is of solid masonry, terminating in the iron plates which form the base of the superstructure. Owing to the immense depth to which some of the cylinders have been sunk, the masonry up to the base of the superstructure is of itself very heavy. To have carried up the pier in solid masonry to the girder level would necessarily have thrown a tremendous weight upon the foundations, and the question which Messrs Barlow had to solve was to reduce the superincumbent weight of the structure to a minimum without weakening the pier. These results have been obtained by the adoption of an iron superstructure of a singularly graceful design. Starting from the base plates at the top of the brickwork, two octagonal columns, each firmly braced inside and plated outside, were carried up till the inner members met in an arch. The other members were continued for a number of feet, and terminated in a base 40 feet in width, to form a bed for the girders. In this way a very substantial pier has been got with the obvious advantage that a very heavy weight has been taken off the basal area. The lattice girder is now almost universally adopted in the building of bridges. The arrangement of the members provides for a very heavy compression strain, while the girder itself is comparatively light. The flooring of the bridge is of steel, and throughout, on both sides of the bridge, there has been erected a girder of close latticework, which serves both as a wind screen and as a protection to persons walking on the bridge. The following tabulated particulars of the bridge will give an idea of the extent of the undertaking.

The dimensions are:

Length of viaduct: 10780 feet

Width of river at site of viaduct: 9580 feet

Height to underside of girders at south side: 65 feet

Height to underside of girders at centre: 77 feet

Height to underside of girders at north side: 16 feet

Number of spans: 85

The numbers and dimensions of the spans are as follows:

11 spans at 245 feet; 2 spans at 27 feet; 1 span at 162 feet; 13 spans at 145 feet; 21 spans at 129 feet; 1 span at 113 feet; 1 span at 108 feet; 24 spans at 71 feet; 4 spans at 66 feet; 1 span at 56 feet; 2 iron arches at 81 feet; 4 brick arches at 50 feet.

The two iron arches span the three skew piers on the north side, while the four brick arches form the approach to the bridge proper on the south side. The abutment and four piers at Wormit carry brick arches of 50 feet span. The abutment itself is of enormous proportions. It is 80 feet in length by 12 feet in breadth, with wing walls 40 feet long. The first, second, and third piers are 12 feet thick at the foundations, and the width is carried up 8 feet 6 inches above high-water mark of ordinary spring tides. At this point the width is reduced by a batter of 1 in 36 to a height of 43 feet to the springing, where the width is 8 feet. These columns are of brick and cement, with hoop-iron bonding. The submerged portions are cased with blue vitrified brick. On these piers are ordinary brick arches, backed by cement concrete. The fourth pier, which may be described as the northern abutment of the arches, is of larger dimensions than the others, as, besides sustaining the brick archway, the southmost end of the first lattice girder also rests upon it. It is 23 feet thick below high-water mark, and, like the others, is carried up by a batter of 1 in 36 to the springing, where it measures 16 feet. The parapet along the arched portion is of solid brick-work, surmounted by a coping of granite. The width of the archway is 77 feet at the southern extremity, and 24 feet where it joins the lattice girders. This was the first portion of the bridge that was erected, and after it had proceeded for some time operations were begun on the north side, and the bridge was erected simultaneously at both ends until the centre girders were reached and the junction was completed. Only some of the girders of the old bridge were utilised in the new structure, and not before they had been severely tested. The materials used in the construction of the bridge make a very reasonable sum total. Of wrought iron 16300 tons have been put into the piers and girders, and if the 118 girders from the previous bridge be taken into account, the total weight amounts to about 19000 tons. The weight of steel used - principally for the floor - is 3500 tons, and the cast iron for the piers weighs 2500, making in all 25000 tons of iron and steel. Ten million bricks have been built into the approaches to the bridge and the cylinders. The bricks weigh 37500 tons, and, if placed end to end, would cover a distance of 1420 miles. The total weight of the concrete used is 70000 tons. In the bridge there are 3,000,000 rivets, averaging about five inches in length. It has been calculated that if these rivets were placed in a line they would extend to 200 miles; or, to put it in another way, they would stretch across the Tay from Wormit to Buckingham Point more than one hundred times.

The estimated cost of the bridge was £640,000, and it was not much exceeded. The founding of the piers was calculated to cost £282,000, and the girders and parapets £268,000, leaving £90,000 for the approaches and arches. Taking the cost of the first Tay Bridge at £350,000, the North British Railway Company has spent fully a million pounds sterling in bridging the Tay. To improve the approach from Newport, the branch line was reconstructed for a distance of half a mile eastward, necessitating the cutting of a tunnel 148 yards long through the hill on the south side of the Newport road. A new bridge was put up at Scroggie so as to give a 30 feet roadway under the line, and these additional works on the Newport side cost £16,000. The work was commenced on 9th March 1882, and on 11th June 1887, the first train carrying passengers passed along the new Tay Bridge. A very careful examination of the structure was made on the part of the Board of Trade, and it was subjected to tests far greater than it is ever likely to bear in ordinary circumstances. The results were highly satisfactory, and on Monday 20th June 1887 - the fiftieth anniversary of Queen Victoria's accession to the throne - the bridge was opened for the conveyance of passengers and for goods traffic.

Back to Fife Pictorial & Historical

Return to: Library Contents