HISTORY OF NEWPORT AND THE PARISH OF FORGAN ; AND RAMBLES ROUND THE DISTRICT, by J. S. Neish, 1890

LEUCHARS

'To Leuchars and back', not by the 'North British', but by the old- fashioned mode of locomotion - on our own feet - is the scene of our last ramble around Newport. The road is so well-known to the residenters of Newport, and to Dundonians generally, that it may seem superfluous to say a word about it, as far as they are concerned. For the information of strangers to the locality it is necessary to state that the village of Leuchars is on the St Andrews Road, about five miles and a half from Newport, and about midway between the Tay Ferry and the ancient University City. Leaving Newport pier, you proceed eastwards till you pass the hotel, and then take the first street on the right at the east corner of the terrace of shops which leads past St. Thomas' Church, and over the hill to the south. This is the great south road, the main line of communication between the Forth and the Tay Ferries, as well as to St. Andrews and the towns and villages on the 'East Neuk of Fife'. For the first two or three miles beyond Newport the scenery along the road is varied and charming. After an ascent of a quarter of a mile or so you get beyond the fashionable villas that line the roadside, and enter on as fine a bit of country road as you could desire. On crowning the ridge the road continues its course over flat tableland for nearly two miles, when it begins to descend towards the level plain that skirts the coast for miles between the Eden and the Tay. Immediately beyond Newport you pass the policies and the east gate of Tayfield House, the fine spreading woods overhanging the road for a considerable distance. You pass Forgan Schoolhouse on the right and the Parish Kirk of Forgan on the left, the latter snugly situated in the centre of a grove of trees and protected from the north winds by a wood-crowned hill. In some parts the road is shaded with fine trees, and at others it is open, and affords extensive vistas of the surrounding scenery, which is pleasantly diversified with hill and dale, and clothed in Nature's richest green. From the parish kirk of Forgan the country descends gradually till the uplands lose themselves in the flat plain that borders the sea coast. A little beyond the kirk a road crosses the main road, and leads eastward to the old kirkyard of Forgan, in the vicinity of which is a grove of old yew trees which are amongst the oldest of the kind in Scotland. The same road leads west by St. Fort, and forms a communication between Forgan and the western parishes of Fife. For a walk or a drive this is an admirable route, as it opens up that part of the country lying between the first and second line of hills that run parallel with the Tay. But our present destination is Leuchars, and we must continue our journey thither.

Nothing of particular interest is to be met with till you get to St. Michael's, unless you chance to encounter some of the numerous bands of the tramp fraternity, with which the road is infested. You may consider yourself fortunate if you escape the whining importunities of these nomads. At St. Michael's the two great roads from south and east converge into the one which leads to the ferry that separates Dundee from the Kingdom. Juteopolis is the great centre to which the genus tramp gravitates, and as he nears the barrier he grows bold and clamorous to get across. Barefooted women and troops of children claim your pity, but the barefaced audacity of sturdy 'unfortunate mechanics', who have been out of employment for goodness knows how long, are the worst to get rid of. They coolly buttonhole you, fix you with glittering sinister eyes, and compel you, however reluctantly, to listen to their tale of woe. A wife and starving children have been left at home far in the south, and with a brave heart and an empty purse he has tramped all over the country 'luckin' for a job'. Dundee is his last chance, the last card he has got to play before he throws up the sponge, but the Tay lies between, and 'cud yez spare a copper to help to pay me boat across'. The last appeal is irresistible, more especially if you have the interest of the Tay Ferries and your own safety at heart; and, after all, the blessings and benisons showered on your head are cheap at a penny.

As you approach Leuchars the scenery changes to an almost dead flat, which extends for miles to east and west. A low range of hills bounding the valley of the Eden hems in the landscape on the south. The highest of these ridges are known by the names of Ardit, Lucklaw, and Craigfoodie; the greatest elevation being about 600 feet. To the east and north stretches the low lying flat known by the name of Tent's Moor. Northward the country is well wooded, while in the vicinity of St. Michael's a large moorland track covered with whins and broom is all ablaze with golden blossoms in the bright spring time.

Leuchars is a flat village, in a flat country. It consists of a row of humble-looking cottages built closely together on either side of the public road. The houses are built of blue whinstone, and are generally one storey high, and roofed with red tile, a peculiarity of the villages in the east of Fife. Here and there you observe a more aristocratic-looking building than the rest, their blue-slated roofs forming a striking contrast to their red-headed neighbours. There is a quiet, sleepy air pervading the whole place; scarcely any of the villagers show themselves in the street; they are a prudent class, keeping their own houses, and their doors shut against strangers. Shops do not appear to thrive, there not being more than two or three with any pretensions to the name, and such 'merchants' as there are do business in their own homes. The railway cuts the village in two, making a level crossing on the main street. In connection with the railway, Leuchars Junction is a place of worldwide fame; here the branch line to St Andrews joins the main line, while the Tay Bridge branch also joined the old line here. Day by day the busy whirl of traffic rushes through the village, but thousands of those who are carried past on the railway every year scarcely know of its existence.

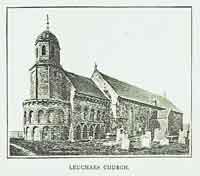

Is there anything to be seen at Leuchars? is a question the reader well may ask. Not very much, we admit, either in or around the village, except the church, which of itself is worth walking five miles to see. On the east of the village, a mound or hillock rises like a molehill out of plain, and the eastern extremity of this hillock is occupied by the church and churchyard. There is nothing striking in the appearance of the edifice as seen from a distance, but on a closer examination it will be found to be a remarkable specimen of ancient architecture. It is supposed to have been built at three different periods, the eastern portion forming the chancel with a semi-circular apsis, in which the altar was placed, having been built about the year 1100. The style is Norman, and with the exception of Dalmeny church, it is the only entire specimen of the kind to be seen in any parish kirk in Scotland. A minute description of the building is given in the 'Statistical Account' of the parish, to which we are indebted for the following: -

'The eastern portion consists of two divisions; the chancel, a square building, to which is added a semi-circular recess called the apsis, which gives a rounded appearance to the eastern extremity of the structure. The apsis is narrower, and not so high as the chancel. Externally the walls are ornamented with two tiers of semi-circular arches, running round the building. There are ten in the lower range and nine in the upper, which are smaller than the lower. The arches are formed of zig-zag mouldings, and rest on plain double pillars. A band or fillet surmounts the first tier, and on this rest the pillars forming the upper arcade. The pillars of the upper tier are placed in the centre of the lower arches, and each pair is supported by a pair of intervening piers. The arches, springing from the upper range of pillars, consist of two rows of stones, the lowest being ornamented with zig-zag, and the upper with fillet mouldings. The intervals between the pillars are filled up with masonry, but in three of the upper tiers small windows have been formed to admit light to the interior. At some distance above the upper arcade the wall projects a little, and for its support there is a range of corbals carved into grotesque heads. The outside walls of the chancel are also formed of two tiers of arches, one above the other, but they are more elaborate and intricate in their details than those on the apsis. The lower range of arches rest on four double and two single pillars on each front, and the top of each alternate pillar is connected with intersecting semi-circular arches, which give the space between each two pillars the form of a Gothic arch, and the effect of the whole is that of a continuous network of arches crossing and interlacing each other. The upper tier rests on a band or fillet immediately above the tower, and they are formed after the design of those in the apsis, with this difference, that the upper pillars stand directly over the lower range of pillars. Above this there is also a row of grotesque faces supporting the projecting upper wall. The roof of the chancel is high pitched, but somewhat lower than the roof of the western division of the building. The roof of the apsis is a conical form, but its original appearance has been altered by the erection of a beehive-shaped belfry, which was added about a century ago. This modern addendum does not tend to enhance the beauty of the structure; it is a clumsy-looking mass of masonry, and to make room for it two courses of stones were taken off the walls, and to support its weight a rude arch was thrown across the interior, which partially obscures the light, besides spoiling the groined ceiling. The interior of the chancel and apsis are in keeping with the exterior, though they have long since been stripped of their ancient glory, and are now used as a bellroom and lumber receptacle. The windows in the interior of the apsis are decorated with pillars of the same pattern as those outside. The roof consists of a simple cross rib of three reeds, with two arches meeting in the centre, and groined between. These arches spring from short pillars supported by corbals, carved to represent the heads of animals. A lofty arch opened into the body of the chancel, and another opened from thence into the nave, the sides of these arches being formed of three slender pillars, the middle one projecting beyond the others, and the upper arches being ornamented with zig-zag mouldings. This was where the altar stood; and the floor is raised a little above the level of the floor of the chancel. The interior of the chancel is lighted with three windows, which are also ornamented with pillars and rich mouldings on the arches. The floor is formed of ancient gravestones, the ground underneath being little else than a tomb. The nave, which is more modern than the chancel, is now used as the Parish Church. Formerly it had an aisle on the north, with an arched opening, but this no longer exists. Part of the walls only remain standing, while the arched entrance has been built up. A massive oak door, studded with iron nails, and bound with strong iron bands, like a prison gate, separates the ancient from the modern part of the buildings. Entering from the chancel by this formidable looking gateway, you find yourself in rear of the pulpit - a low set, plain looking rostrum - with the whole body of the church, a long, narrow building, stretching out before your eyes. Internally it is as plain and simple as the strictest Presbyterian could wish. There is a gallery on the west end, which occupies about a third of the entire length of the church. The roof is painted a light oak colour, the walls are whitewashed, and the interior is lighted with rows of tall Gothic windows on each side.'

The most eminent minister whose name is associated with Leuchars Parish Kirk is the Rev. Alexander Henderson, the Knox of the Second Reformation - the great struggle between Prelacy and Presbytery, which began in the reign of Charles I. and ended in the triumph of the latter at the Revolution. In early life it is said that Henderson had a strong predilection for the Prelatical party. He was presented to the living at Leuchars by the Archbishop of St. Andrews, but the parishioners opposed his settlement, and he had to be forcibly intruded into the charge. On the day of his ordination the church was locked against him, and he and the brethren of the Presbytery had to climb into the building by a window. Shortly after this he was converted to Presbyterianism, and to something better, by a sermon he heard preached by the Rev. Mr. Bruce of Kinnaird. Henderson crept into the church where Bruce was preaching, and ensconced himself in the darkest corner. The preacher selected as his text the words - 'He that entereth not into the sheepfold by the door, but climbeth in by some other way, the same is a thief and a robber' - a very suggestive text in such a case as his - and the sermon which followed told upon him with power. Henderson renounced his Prelatical opinions, and soon came to the front in the great struggle. For twenty-six years he was minister of Leuchars, and then he was removed to Edinburgh. He spent a busy life, and was cut off in the midst of his labours. Henderson was one of the Westminster Assembly of Divines, the proposal to hold that Assembly having been suggested by him. It is also said that he drew out the Solemn League and Covenant, and exerted his influence on the people to induce them to sign that document. The last work in which he engaged was a debate on Church government with King Charles I.

From the church we naturally wander into the churchyard. There is a fascination about churchyards which attracts even a thoughtless wanderer to pause and ponder on the lessons of immortality which such a spot is calculated to teach. Then

'Come, come wi' me to the auld kirkyard,

I weel ken the path by the soft green sward,

Friends slumber there we were wont to regard.

And we'll trace out their names in the auld kirkyard.'

Commend me to a genuine auld kirkyard - not your modern cemetery, with its trim-kept walks and pretentious monuments ranked in lines with military precision, and its graves adorned with parterres of flowers like an ornamental flower garden. No, not that, but a real old village kirkyard, where the little mounds and moss-covered tombstones lie scattered over the ground in sublime confusion, and the long rank grass waving in wild luxuriance, and docks and nettles grow thick in neglected corners. Such a kirkyard as that surrounds the old kirk of Leuchars. In the midst of such a spot you seem to stand as it were between the living and the dead - the past and the present with all their associations meeting around you. Beneath those grassy mounds moulders the dust of many generations of men and women who have played their part in the drama of life, as the present generation are doing now. Each had their little history, and were borne to the grave by mourning relatives just as the humble surfaceman who met his death while pursuing his daily avocation on the railway track, whose remains were laid beneath the sod in the churchyard of his native place on the very day we visited the village.

Leuchars kirkyard is peculiarly situated. It stands like an island in the plain at the extremity of the village, encircled by roads, and hemmed in by houses on the north like a rampart. On that side the houses are built with their back walls on the face of the brae, which must have been cut plumb to allow the building to rest against it These houses are, with the exception of one in the centre of the row, all one storey, and their red tiled roofs slope down almost to the level of the graveyard. Strange that such sites should have been selected for building cottages, as their floors must be lower than the level of the deepest graves. By the laws of sanitary science such abodes must be pesthouses of disease, and yet they are all tenanted, and their occupants apparently in the enjoyment of good health.

A little to the north of the village is a curious mound of earth, about an acre in extent, and planted with yew trees, on which, in former times, stood the Castle of Leuchars. It was an ancient fortification, and was supposed to have been built by the Picts. In later times it was a stronghold of the Earls of Fife. It was built on the edge of a marsh, and was surrounded by a deep moat, and was a place of great strength. Nothing now remains of this ancient fortalice but its site, which is believed to be artificial. What is known as the lodge of the old Castle has been converted into a fine country mansion, and bears the name of 'Leuchars Lodge'. It was the property of the late Mr. Isdale, a Dundee merchant, who greatly improved the house, and laid out the grounds in a tasteful style. A marshy piece of ground, lying between the mansion and the public road, has been taken advantage of, and converted into a circular sheet of ornamental water, with a wooded island in the centre. The house and grounds, with the ornamental water, are situated on the north side of the road as you approach the village from Newport, and they add much to the beauty of the district.

About half a mile south-east from the village, on the St. Andrews road, is the old mansion house of Earlshall, finely situated amongst grand old woods. It is a remarkable place, and well worthy of a visit. Originally it was one of the seats of the Earls of Fife, from which it derived its name. In later times it came into the possession of a branch of the Bruces of Clackmannan. One of its owners figured in the Covenanting persecutions, and was known as 'The Bloody Bruce of Earlshall' - a name synonymous with that applied to his friend Claverhouse. The old house is now deserted, and in a semi-ruinous condition. The chief object of attraction about the building is a large hall, the walls of which are covered with beautiful carvings and quaint and curious inscriptions. You may return again by the road you came, but a good pedestrian with time to spare may vary the scenery on the homeward journey by taking the Tayport road at St. Michaels. About a mile on this road another road branches off to the west along the valley, and, passing the old kirk and kirkyard of Forgan and the manse, joins the main road again about three miles from Newport This, of course, will lengthen out the journey by three miles or so, but those who have never seen Forgan kirkyard and the Kirkton yew trees will be amply compensated for the extra fatigue.

Previous Introduction I II III IV V VI VII VIII IX X XI XII XIII Tayport & Scotscraig Scotscraig (continued) Kilmany Balmerino Leuchars Addenda Name Index Next

Return to: Library Contents